How did the Old Quarter begin and evolve through history?

There's an old Vietnamese saying, "Hanoi has thirty-six streets and guilds - Jam Street, Sugar Street, Salt Street...."

Many folk songs and poems also allude to the traditional numbering of the Old Quarter's streets at thirty-six.

However, few people notice that the number thirty-six has not always accurately reflected reality.

During different historical periods, the Old Quarter had a varying number of guilds associated with specific streets. Furthermore, the number of streets depends on how one counts, that is, how one interprets the historical record. A "street" differs from a "guild." During the Le Dynasty (fifteenth to eighteenth centuries), the "guild" denoted an organization of people working in the same trade as well as an administrative zone of the old Thang Long (Hanoi) Citadel. The guilds tended to give the names of their trades to the streets where they did their business.

According to historical records, the citadel during the Tran Dynasty (1225-1400) had sixty-one guilds, but the figure dropped to thirty-six during the Le Dynasty. These guilds were of three kinds: agricultural, handicraft, and merchant.

The Du Dia Chi (Treatise on Geography) written by Nguyen Trai in 1438 says, “Thuong Kinh is the capital. It has one town named Phung Thien and two districts, Tho Xuong and Quang Duc. Each district has eighteen guilds." The Treatise also mentions several places located in present-day Hanoi’s Old Quarter. Nguyen Trai noted, for instance, that Hang Dao Guild engaged in dyeing red silk and Ha Tan Guild (modern Hang Buom), in baking limestone.

Given Nguyen Trai's remarks and other historical information, we can conjecture that Hanoi's Old Quarter came into being at the time King Ly Thai To selected Thang Long as the country’s capital in 1010; we know it became a crowded and lively place after the fifteenth century. The streets generally retain their old names today, even though in most cases their original functions have shifted location or ceased to exist.

“Vu Trung Tuy But” (Collection Written on Rainy Days) written by Pham Dinh Ho in the late eighteenth century says, "Thang Long Citadel is composed of thirty-six guilds."

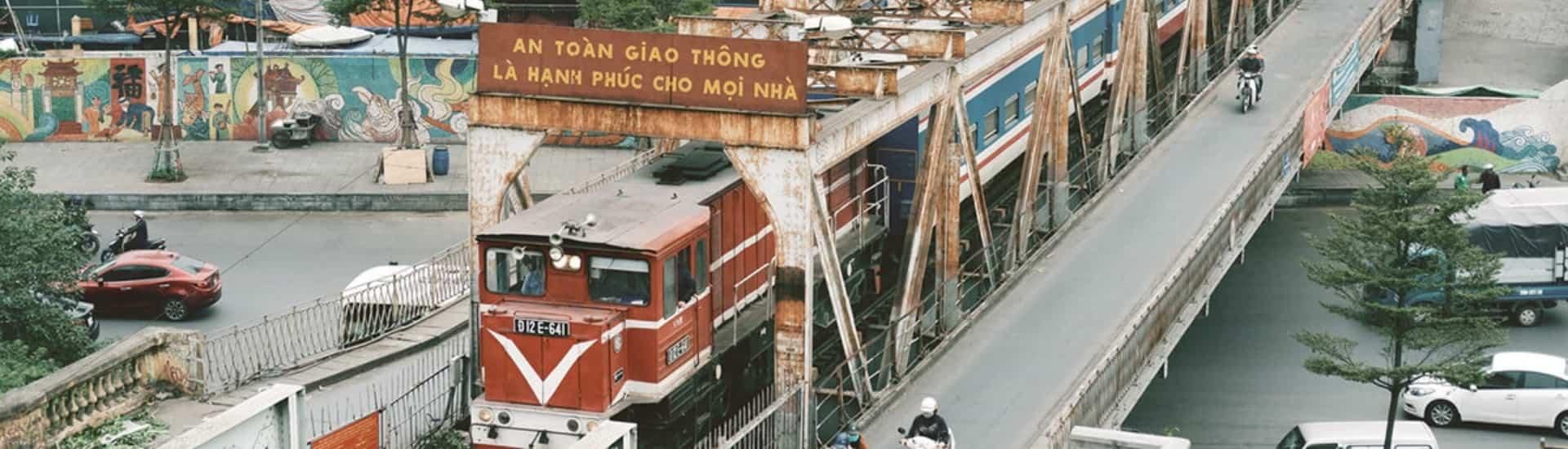

Although Hanoi's Old Quarter has a 500-year history, few buildings in the architectural style of the Le Dynasty remain except for several pagodas and communal houses. Most houses and shops were built of mud bricks; they failed to survive the destruction of time. Even where brick structures have survived, their wooden stairs, doors, and window frames are newer. Weather and termites damaged the original.

Most of the houses modern visitors see in the Old Quarter were built at the end of the nineteenth century. But since many of them were erected on their former foundations, they continue to exhibit many architectural characteristics of the buildings that preceded them. The most distinctive of such characteristics, at least for domestic architecture, is the so-called "tube house," whose long, narrow structure resulted from a lack of space within the old city and an imperial tax calculated by the width of shop frontage. These dwellings, which no doubt evolved from early market stalls, are often only two to three meters wide, but they may be 50 to 100 meters long. Some houses have frontage on two parallel streets.

In the old days, one extended family occupied each house, but modern times have forced the residents of the Old Quarter to subdivide the old tube houses. Now, a family of four commonly lives in a space of from fifteen to twenty square meters.

The portrait studio at 51 Hang Dao retains many qualities of the older buildings. A visitor can feel the way life was a hundred years ago by peering into this shop. Those deeply interested in architecture might even consider having their portrait drawn in order to have a better look.

All of the long narrow houses had interior courtyards in the old days, though residents have covered many of these over for storage or living quarters. Though small, these courtyards provided light and air and a quiet place for elderly family members to drink tea, cultivate ornamental plants, or raise pet birds and fish. The population explosion has consumed the courtyards. Now, residents use every square meter for commercial purposes or to house their families.

Temples such as Bach Ma (located on Hang Buom) date to an earlier period and predate even the old guilds. Bach Ma, with foundations dating from the ninth century, is dedicated to the white horse said to have shown King Ly Thai To (974 - 1028) the correct position for his citadel walls.

In addition to influencing domestic architecture, the old guild system also contributed distinctive public buildings, including temples and communal houses for the various clans that had moved in from the countryside. Guild members invariably built temples to commemorate the founder of their trade or craft. Many of these still exist.

“A Dinh” (communal house) at 64 Ma May Street retains its original features. Ma May presents, in fact, a very interesting architectural tour all by itself. In addition to the Dinh, a beautifully restored house at 87 Ma May is open to the public.

The twentieth century also left its characteristic styles, from Soviet modernism to the elaborate faux French facades of the early renovation period, to what might be called the "boutique architecture" of the 1990s, with its slick stone and expanses of glass.

In Civilisation and its Discontents, Sigmund Freud likened the human mind to his favorite city, Rome. The mind, he wrote, contains layers invisible to consciousness just as the earlier layers of Roman civilization lay buried beneath the modern metropolis. Those buried streets and monuments represent our unconscious minds, he said, affecting our beliefs and feelings even though they can no longer be seen. Had Freud visited Hanoi's Old Quarter, he might have modified his theories: here, although much doubtless lies buried, many older layers remain available for contemplation.

What is the role of Dong Xuan Market in the life of Hanoi?

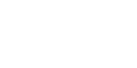

Dong Xuan, Hanoi’s largest market, is in the heart of the Old Quarter and part of an ancient hamlet with that same name. The French colonial administration built the market in 1889 to replace the Cau Dong (Eastern Bridge) Market to the east. Roofed with tin, it comprised five large halls.

Boats brought goods into the city on the Red River, which flows nearby. Trams stopped at its front entrance.

Products came to Dong Xuan from all over the country. In its early days, wholesalers used the market as a distribution center for retailers. Goods piled the market, which teemed with buyers and sellers, offering a picturesque sight that attracted French colonists in search of the exotic.

However, colonials were not the only ones who found the market fascinating. At the turn of the century, Hà Nội with its brand new electric lights and its famous Đồng Xuân Market produced a stunning effect for a peasant arriving from an uneventful and impecunious life in the countryside. According to a popular verse from the time,

Hanoi is like a grotto for fairies

At six, lamps twinkle everywhere

The most fun is Dong Xuan Market

Trading goods from near and far...

By the 1930s, traders of some standing, mostly women, occupied the central hall. Dealers in fabrics sat on plank beds; vegetable hawkers hunkered behind big baskets filled with apples, oranges, and other fruits imported from Hong Kong and San Francisco; vegetable sellers displayed such luxuries as cauliflower and celery grew at high altitudes Sapa and Dalat.

Other stalls sold food specialties such as spring rolls (nem), noodle soup (phở), roast pork, and round rice noodles with crab meat (bún cua).

These were also haberdashers (mostly Chinese); merchants offered porcelain, ornamental plants, traditional medicines, betel, areca nuts, and wickerwork; and a dozen or so fortune-tellers of both sexes, either blind or supposedly so, tended passing buyers.

Dong Xuan has evoked rich memories for poets and writers. The novelist and essayist Thach Lam (1909-1942) described a tea-stall set up by a young woman named Dan in front of the market: "There was little displayed at her stall: a few betel quids, some packets of tobacco for water pipes, a couple of cigarettes, and several crockery tea-bowls turned upside down just like in every tea stall throughout Vietnam. ... After finishing a meal with rice wine, everyone likes to have a cup of hot tea. ... Some stalls are popular for the goods they offer, while others are famous for the young women who sell. Tea stalls most characterize the personality of the Vietnamese lifestyle... Many novels have started in a tea stall and have also ended there."

Following the defeat of the French in 1954, the Government controlled the economic system; Dong Xuan Market became less active until the late 1980s and the policy of economic renovation.

French journalist Françoise Corrèze noted: "The market was full of scents that wafted to your face and heart, enough to make you dizzy: cinnamon, saffron and, here and there, a whiff of pepper or ginger. And of course, there were fruits: banana, papaya, mandarins, and oranges more green than sun-tanned and often with a granular skin."

Hanoi's population increased tenfold in a century. The city rebuilt Dong Xuan Market in 1990 while keeping its former front. Unfortunately, that market burned in July 1994, causing damages estimated at US$17 million. It was rebuilt a second time and inaugurated in December 1996. Today, the market is cleaner and more orderly, though without the past's picturesque anarchy.

How do people live in the Old Quarter?

Living is sharing. This may be nowhere truer than in Hanoi’s Old Quarter.

The house at 51 Hang Dao, for instance, was built in 1930 for one family, its ancestral altar, and the family silk business. Although built later than the "tube houses," that architectural tradition influenced its structure. The ground floor contains a shop, common room, sleeping room, inner yard, kitchen, backyard, and toilet. The upstairs has a small room, a courtyard linking the roofs of the house, a room for ancestral worship, and a large yard for silk drying. The house is three meters wide and fifty meters long. Sunlight enters through open yards and courts, creating a pleasant atmosphere.

Then in 1954, after the defeat of the French, a second family of eight moved into the house, living in the outer room of the upper floor while the former owners occupied the rest of the house. Since the house is narrow, the second family had to pass through the first family's space to reach its own quarters. Both families shared the inner yard, kitchen, and back garden.

Now, the house is a portrait-drawing business operated by three artists. The shop itself is in the room facing the street, while the room behind serves as the drawing workshop. Three generations live in the house. The grandfather helps two of his children run the shop in the evening. Others in the household earn their living outside the Old Quarter.

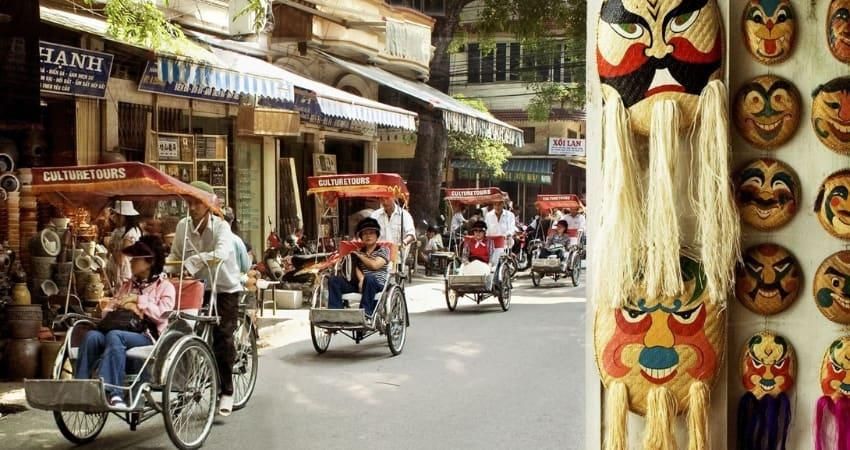

Close living quarters still play an important role in the life of the Old Quarter. Ideally, the community recognizes each individual's needs, reducing potential conflicts that could breed from living closely together. People tend to help each other in small matters such as shopping, cooking, and looking after each other's houses and children. Important events such as weddings, funerals, and death anniversaries become major opportunities for community involvement.

Most of Old Quarter's inhabitants run businesses. They open their shops at 8:00 every morning and do not close until late in the evening. During the long workdays, merchants also engage in many other activities: eating, chatting with fellow traders and neighbors, watching TV, and taking care of children.

One of the most pervasive and enticing aspects of the Old Quarter is its variety of food. Ready-to-eat meals constitute a large sector of economic activity. At times it seems as if half the Quarter's residents are preparing food for the other half. Some street vendors have sold food in the Quarter for decades, following the same itinerary every day at exactly the same hour.

Foods commonly served in the morning include round rice noodles with snails (bún ốc), steamed sticky rice, rice crepes (bánh cuốn), noodle soup (Phở), and round rice noodles with duck meat (bún ngan). Around noon, light meals predominate, including ground pork pate (giò) and grilled chopped meat (chả). In the afternoon, vendors offer cakes, steamed sticky rice, and sweet puddings. For generations, these foods and activities, which change throughout the day, have produced a comfortable life rhythm.

The Old Quarter does not have rows of huge trees typical of other parts of Hanoi. Nevertheless, the residents make room for nature by growing ornamental plants sun on narrow roofs, balconies, kitchens, and in the rare small yards that are highly refuges valued from the street noise. Dogs, cats, and ornamental birds share the cramped Old Quarter with their owners.

Although life in the Old Quarter is cramped, residents choose to stay; they don't want to exchange the small houses in which their families have lived and done business for generations for larger places away from the district.

Why is Hanoi’s central lake called Hoan Kiem Lake (Restored Sword Lake)?

During the domination by the Ming Chinese (1406-1428), a fisherman named Le Than lived on the Chu River in Thanh Hoa Province. One night, Than's net felt heavy when he hauled it up; he grew excited, thinking he'd caught a big fish. However, Thân soon saw that his "catch" was only an iron bar like a blunt knife without a handle.

"Ah me," Than sighed. "My only catch tonight is a worthless piece of iron!" Than threw the bar away.

Another night, Than cast his net in another section of the Chu River. After a while, seeing the water bubble, Than pulled up his net but found only the same iron bar. Angry, he threw it away once again.

Then came another night; Than went fishing late. At cock's crow, he pulled up his net and, feeling it with his hands, found the same iron bar. However, this time he decided not to throw it away. Than pulled the iron bar onto the deck of his boat and lit a fire to take a closer look. Now, he could see more clearly.

it's a sword blade!" he exclaimed.

At this time, people from all over the country were joining Le Loi's army to fight the Chinese. Every night, Le Than heard blaring horns and the commanders' voices shouting to their soldiers on the banks of the Chu River. He looked at his sword blade and said to himself, "God wants me to help save my country."

He abandoned his boat and joined Le Loi's army. One evening, the army stopped to spend the night in the forest. He was on guard duty when Le Loi, who was passing by, saw something shining. Out of curiosity, Le Loi stopped at Le Than's camp. Le Than took down the sword blade and showed it to Le Loi, who stared at it.

This is a magic sword blade!" Le Loi said. "Except it lacks a matching magic hilt."

Soon after that night, Le Loi and his followers lost a battle; they retreated into the forest, each man finding a place to hide. Le Loi took shelter on the branch of an old banyan tree. He noticed streaks of light on a nearby branch; these looked like fireflies or the flashing scales of a python. Le Loi slid over for a closer look. At first sight, he mistook the strange light for a phosphorescent centipede on a piece of rotten wood. He picked up the object; it turned out to be a sword hilt made of a horn. Its inlaid gems glistened.

Le Loi remembered the sword blade he'd seen in Le Than's camp and tucked the hilt into his belt.

When the army reassembled, Le Loi told everyone about the hilt he'd found in the forest.

He took out the hilt and matched it with Le Than's blade. The two fit perfectly. Le Than and everyone else knelt.

"God has bestowed on you this magic sword!" the men shouted.

Le Loi's army regained its strength and pressured the Ming troops into retreat. Using his magic sword, Le Loi won battles against the invaders until the Ming finally surrendered. After ten years of fighting, Le Loi's army achieved its glorious victory in 1427. Le Loi became king and unified the nation; the people lived in peace.

One beautiful day, Le Loi took a boat trip around the Luc Thuy (Green Water) Lake in the center of the capital. It was early autumn; the lotus leaves were as green as the water's surface. Suddenly, a huge tortoise emerged from under the lotus leaves. It had a raised back and looked as black as a bamboo dinge. The tortoise swam slowly toward the king's boat. Then it raised its body, clasped its two front legs together, and bowed. "Now that you have restored peace to the nation," the tortoise said, "please return the sword to our God of the Waters."

Le Loi immediately took the sword from his belt and respectfully raised the weapon above his head. Then he bowed. The tortoise accepted the sword and disappeared into the water, but the luster of the sword remained and spread over the surface of the lake. Ever since that time, the lake has been named Ho Guom (Sword Lake) or Hoan Kiem (Restored Sword Lake).